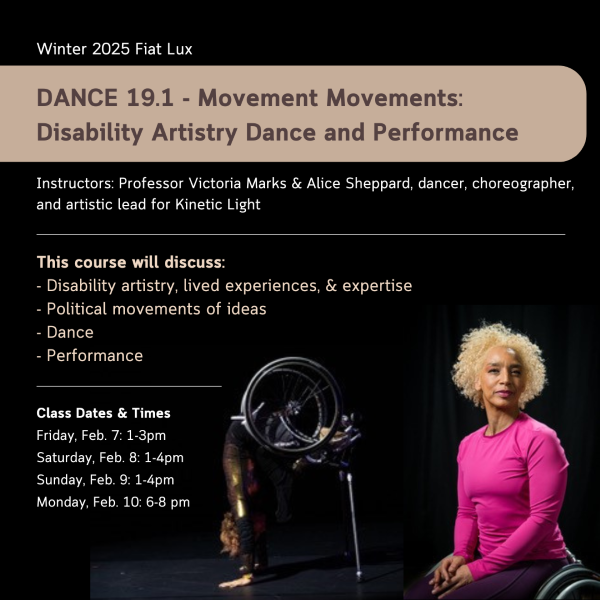

Victoria Marks, associate dean of the UCLA School of the Arts and Architecture, professor of choreography and chair of the disability studies minor, has been teaching at UCLA since 1995. An Alpert Award winner, Guggenheim and Rauschenberg Fellow and Fulbright Distinguished Scholar, Marks has been creating dances on stage and film for 37 years. She serves as faculty chair for UCLA’s experimental Dancing Disability Lab and continually explores the representation of disability through her work.

What is the Dancing Disability Lab?

The Dancing Disability Lab is a seven-day intensive that brings in artists from all over the world who identify as disabled dancers. In the inaugural session this past June, participants came from New Zealand, South Africa, Canada, and across the U.S., all with very different embodied experiences. It was like a hothouse of thinking — a research lab.

Could you describe a typical day during the intensive?

We’d start in the morning, gathering for breakfast and a seminar with Rosemarie Garland-Thomson, who is a disability studies scholar and bioethicist at Emory University. She would have prepared a visually illustrated presentation, addressing art made by artists with disabilities and inviting us to consider representation and embodiment. We’d think about these issues and then go into a movement class with Alice Sheppard, one of the artists involved in the Dancing Disability Lab. This was followed by an improvisation and composition workshop to explore these questions through the body. And then we’d come back at the end of the day to sit around the table and discuss how our actions and ideas created productive frictions with one another. We examined how we might take the conversation a step further.

When did you begin working with disabled and nondisabled dancers? How did the experience influence you as an artist?

When I was living in England in the early 1990s, I collaborated with filmmaker Margaret Williams and Candoco, a company of disabled and nondisabled dancers, on the film Outside In, which was a threshold moment for me as an art maker. It made me think about disability in a whole new way.

It also made me think, “Why do we make art that is about ideas out there [gestures far away] when everything we need to attend to is right here in the room?” When I worked with Candoco, I was making an action portrait of the dancers — not only who they were, but also who they wanted to be. I started thinking about myself as a portrait artist. I really like the idea that the people in the room are intrinsic to whatever gets made. And that’s always true, because dancers are always participant in the process when I make dances — their imprint is everywhere. Working with Candoco changed my thinking about dancemaking in general.

The Dancing Disability Lab gathers dancers who all identify as disabled. As a nondisabled choreographer, what’s your role in the creative process?

There’s a shift that is happening in the field: It’s time to think about what happens when disabled dancers get together to make art. This is in addition to the continued and important work of physically integrated dance groups. It’s important to ask, “How does the experience of disability inform what artists make, and how does that impact all of us?” As a nondisabled choreographer, I can facilitate and create structures for others whose differently embodied experience will be valuable to all of us. My role is to facilitate new conversations in the field. The Dancing Disability Lab is an opportunity to start thinking about what “disability aesthetics” in dance might be.

Do you have a personal connection with dance and disability?

I have always resisted the notion that dancing is primarily about technical virtuosity. I don’t dance full out anymore because of injuries, but I don’t think of myself as disabled, as much as I note the tremendous instability of “ability.” Aging brings with it gains and losses. I have a son with autism and other neurological issues. That does not drive my commitment to dance and disability. We all have people in our families who experience life differently. I’m moved by people caught in the midst of living. What is sublime is the pursuit of vitality and connection with others.

What were some of the discoveries that arose during the inaugural intensive?

In so many ways, it’s just the fact the dancers are coming together and dancing together and finding new paradigms for engagement. A dancer [who is] not trying to locate themselves within an ability-based norm and function inside of that embodies the self as they are, finding new relationships to time, new discoveries about being at home in space, and new ways of constructing intimacies with others. [They] invite us to think differently about power [as they] interact with their walker, cane or other prosthetic-expanded body, speeding faster in a wheelchair than anyone can run.

What is an example of an assumption that disability in dance challenges?

I think the disability experience adds a dimension to lived experience, including environments. Alice Sheppard has this really exciting piece called DESCENT, for which she built a set that is a beautiful ramp that she and her partner, Laurel Lawson, dance on in their wheelchairs. The Dancing Disability Lab is a place to start to think about what happens when our minds open up through the expansion of human experience.

What interests you now?

I feel strongly about the importance of representing different bodies on stage. I’d like to create more pathways for dancers with a range of embodied experiences to get a dance degree. We have opportunities to rethink relationships between the body and subjectivity, and a spectrum of what it means to be human. Dancing holds a mirror to who we are and who we aspire to be. In this sense, I am interested in supporting our collective aspirations toward inclusion and in setting up experiences that help us to get there.

What opportunities do audiences have to retrain their way of seeing?

That’s a good question. I think I have to look at the way we are already trained to see. It’s probably safe to say that most of us have tremendous anxiety about our bodies — our appearance, our smells, our sounds. This likely translates to the way we view others, including who is desirable, who has status and who will get great jobs. Viewpoints that discriminate against differentness are taught, and we become so habituated to them that they become invisible. When artists wake us up with perspectives about humanity’s diversity, we learn to see differently.