By: Rachel Hale

View the original article on USA Today.

Russell Lehmann wasn’t diagnosed with autism until fifth grade, but he says the signs were there earlier. He remembers crying when he had to leave his mom’s side to go to school and struggling to fit in with other children.

The diagnosis came after he spent five weeks in a psychiatric ward as he grappled with severe OCD and phobias after dropping out of school. The educational neglect and social trauma he experienced as an autistic student with OCD, depression and anxiety led him to withdraw from the world for the next 15 years as he took online courses, failing on three separate occasions to reintegrate into public school.

“I was conditioned to be ashamed and hide who I was,” Lehmann says.

He felt “completely forgotten by the world,” and he says he’s not an outlier. Today, as a public speaker and UCLA Disability Studies Professor, he focuses on spreading awareness about the intersection of disabilities and mental health.

‘Completely forgotten by the world’

Lehmann’s phobias led to extreme isolation in youth, to the point where he rarely left his house. He wanted to join in with others, but there was no support to bridge the gap, he says.

“Emotionally and mentally, I’m a living and walking oozing wound,” Lehmann says.

Children with disabilities are more likely to face mental health issues and experience stressful life events – such as abuse, neglect, household instability or exposure to violence, according to the CDC. Events experienced in childhood can have a long term impact on the transition to adulthood, including employment education and relationships. They are also at a higher risk of experiencing trauma, in part because of factors like discrimination or limited access to resources.

Lehmann experienced long-term effects from his childhood isolation and struggled with a lot of “bitterness and resentment” throughout his 20s as he tried to take part in things like friendships and dating, which he says often led to heartbreak.

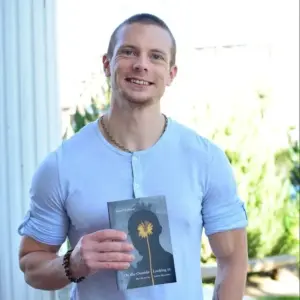

During a bout of deep depression in 2012, he found solace in Edgar Allen Poe’s writing. He started exploring poetry as a form of self expression, and he published “Inside Out: Stories and Poems From an Autistic Mind” about his journey. In his late 20s, he started public speaking to share his journey, and in a 2022 he gave a TED Talk.

‘Just existing in that world is traumatic’

Lehmann says there’s a “huge misperception” about how disabilities manifest on a day-to-day basis. Teachers commonly misunderstood his methods of self-regulation, such as stimming by flapping his hands, as a threat.

“I was just the square peg trying to fit into that round hole, always forced or berated if I didn’t make eye contact with the teachers as if I was being disrespectful,” Lehmann says.

Some autistic individuals may attach themselves to inanimate objects, which can serve as a coping mechanism in overwhelming settings. He recalled it felt like losing his best friend when his teacher took away his toy ball.

“They thought I was just goofing off, throwing a ball in the air and not wanting to do my work, when that was actually helping me to function,” Lehmann says.

When educators lack training and knowledge of how disabilities may manifest, it can lead to unnecessarily extreme outcomes, according to Robyn Linscott, the director of education and family policy at The Arc, a non-profit advocacy group for individuals with disabilities.

“If you don’t know that this behavior is a manifestation of that child’s disability, then you could interpret it in a way that could lead you to escalating the situation, potentially leading you to something that becomes more physical and more dangerous,” Linscott says.

To this day, meltdowns are an important way that Lehmann regulates his nervous system. A meltdown is a reaction to an overwhelming sensory experience and might manifest in hyperventilating, sweating and crying.

Lehmann has shared footage of those meltdowns to his nearly 44,000 Instagram followers as a way to de-stigmatize the reactions.

View this post on Instagram

But the intense scrutiny he faced in the classroom and public settings over time led him to be “unconsciously conditioned to mask all the time.”

“I liken my life to a play. I can show up and perform quite well, but nobody sees the blood, sweat and tears behind the scenes that go into just simply showing up just so I can function,” Lehmann says.

Murphy King, 24, who is autistic and is a recent graduate of Harvard University, recalled their educational experience as being “uniquely lonely.” They say they felt significant pressure to mask in high-performing academic spaces.

“The single greatest barrier to my mental health in the present day is that I have no idea what my actual needs are, because I’ve spent my entire life masking to perform in such spaces,” King says.

From school drop out to UCLA

In January, Lehmann started teaching a UCLA course for disability studies and psychology majors on the medical model versus social model of autism and neurodiversity. Lehmann says the rise of the social model, which focuses on the social and environmental factors that impact disability and on breaking down roadblocks that “disable” an individual, has been one the largest strides made since he was in school.

At times, he says being on campus is painfully ironic given how his dreams of attending college never transpired.

Seeing the inclusion and accommodations given to autistic students that he lacked for so long is bittersweet — today, a hub of online spaces exists for autistic individuals, and Autistic Pride Day has grown in popularity since it was introduced in 2005.

“We’d like to think we have come so far, and we have, but the bar was so low to begin with,” Lehmann says. “We still have a lot of work to do.”